Gary Kevin Shepherd

United WorldI want to make clear right at the outset what I mean by saying this is not a standard review of the book “When the World Outlawed War” by David Swanson. By that I mean that I am not offering a critiques of the book itself, although I will touch on aspects of the book, but rather analyzing the underlying theme that the book is presenting.

Swanson begins his book by quoting from an old 1950s folk song: “Last night I had the strangest dream I’d never dreamed before. I dreamed the world had all agreed to put an end to war. I dreamed I saw a mighty room and the room was filled with men. And the paper they were signing said they’d never fight again.” But as Swanson points out, by the time the song was written, it wasn’t just a dream. On August 27th, 1928, the majority of the nations of the Earth, including the United States, had come together to sign a treaty called the Pact of Paris, or the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which declared that war was illegal.

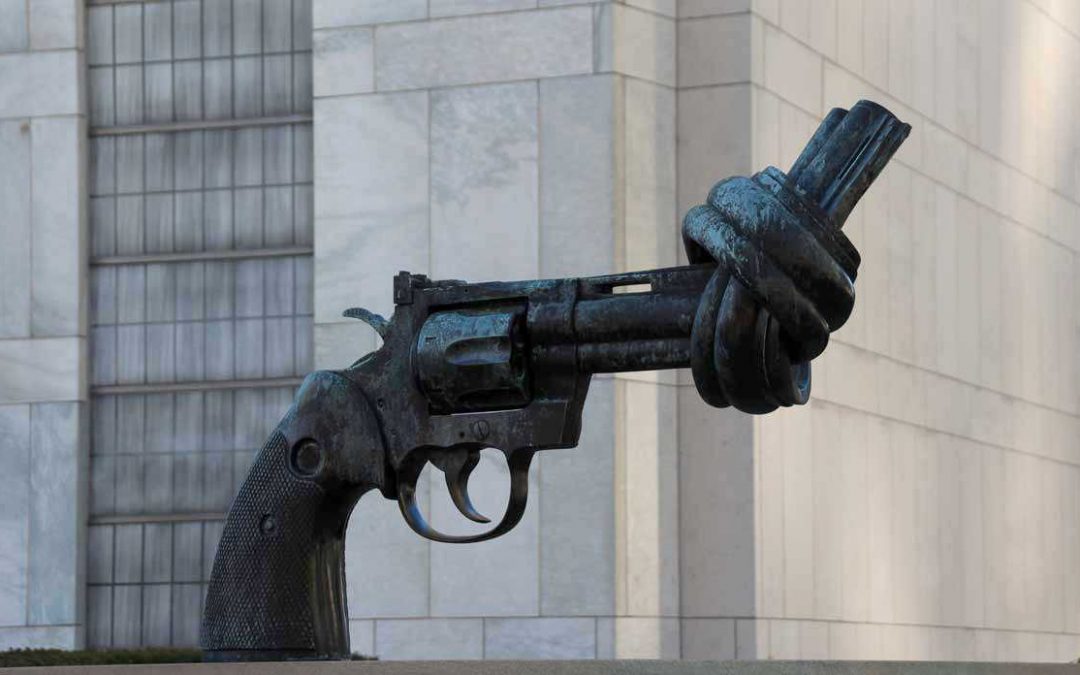

Kellogg-Briand Pact a treaty agreement to outlaw war

The guts of the Kellogg-Briand Pact is actually very simple. Its authors wisely declined trying to differentiate between ‘aggressive’ and ‘defensive’ wars, or ‘just’ and ‘unjust’ wars, precisely because they knew every nation always thought the wars it was fighting were just and defensive. The operative part of the treaty consists of just two sentences: “The High Contracting Parties solemnly declare in the names of their respective peoples that they condemn recourse to war for the solution of international controversies, and renounce it as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another. The High Contracting Parties agree that the settlement or solution of all disputes and conflict of whatever nature or of whatever origin they may be, which may arise among them, shall never be sought except by pacific means.”

Surprising number of nations want to outlaw war

This Treaty, which was ratified by the United States Congress by a vote of 85 to 1, is still in effect and Swanson argues that it constitutes a declaration that war, all war, is therefore illegal. He is not alone in that contention, for one of the charges brought against the Nazi regime at the Nuremberg Trials following World War II, was that they had violated the Kellogg-Briand Pact, which Germany had also signed. In addition to Germany and the United States, two of the original signers, the following countries are currently party to the treaty: Afghanistan, Albania, Antigua and Barbuda, Australia, Austria, Barbados, Belgium, Bosnia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, Columbia, Costa Rica, Cuba, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominica, the Domincan Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Estonia, Ethiopia, Fiji, Finland, France, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, India, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Liberia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherland, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Saudi Arabia, Slovenia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, the United Kingdom, Venezuela, and most of the former states of the Soviet Union. Many of these countries did not even exist in 1928.

Treaties don’t work — too easily ignored or broken

The Kellogg-Briand Pact has been largely forgotten by history. I doubt that one in hundred people have ever heard of it. Those few know about it, generally regard it as a failure. But this view is not held by everyone. In an email, I once told someone that their efforts were as potentially important at the Kellogg-Briand Pact. I had meant it sarcastically, but they took it as a compliment.

I had originally started reading this book in order discover how the activists who brought it about managed to succeed. I thought that there might be something to learn from their efforts, and if it was an example that we could follow, a hundred years later. .But I am not sure it could be emulated, even if we wished to do so. The social and political circumstances that gave rise to the ‘outlawry movement’ were unique. The industrialized brutality of the First World War had shocked people, and they were eager to find a way to avoid its repetition. This was particularly true of Americans who had taken to heart Wilson’s propaganda about it being “a war to end all wars”. There was a feeling that just as slavery and dueling and saloons had been abolished (this was during Prohibition, after all) so the advance of civilization could also bring an end to war.

Because of its basic simplicity and moral clarity, the outlawry movement appealed to a wide coalition of people: liberals and conservatives, Republicans, Democrats and Progressives, atheists and religious groups of all stripes, internationalists and isolationists, and those who opposed the League of Nations as well as those who supported it. Critical to the movement was the enthusiasm of the newly minted women voters. Powerful institutions, such as the major newspapers were overwhelmingly favorable to it. So fierce was the popular appeal that even those who despised pacifism, such as the U.S. Secretary of State Frank Kellogg himself, were pushed into supporting it.

The problems with the Pact were apparent from the beginning. The Pact contains no language on how it should be enforced. Kellogg and others rejected the idea of putting ‘teeth’ in the treaty language, because the only way they could see to enforce it was to agree to declare war on violators. That was something they regarded as not only politically distasteful, but morally repugnant. “You cannot use war to make peace,” they argued with perfectly sound logic.

Public pressure needed, but not enough to outlaw war

So what they attained was basically a solemn promise not to make war. And they earnestly believed that was enough. It was not that they were ignorant of the concept of a global regime to enforce peace. In his speech accepting the Nobel Prize, Kellogg even said, “I know there are those who believe that peace will not be attained until some super-tribunal is established to punish the violators of such treaties, but I believe in the end the abolition of war, the maintenance of world peace, the adjustment of international questions by pacific means, will come through the force of public opinion, which controls nations and people – the public opinion which shapes our destinies and guides the progress of human affairs.”

But public opinion can be manipulated by those in power – as Hermann Goering so eloquently and bluntly pointed out during his own trial for war crimes. Moreover most of the evils that humanity has ended, have been brought to an end not just by adverse public opinion, but by laws – that is, by a system of regulation under which violators are apprehended, tried and punished. One can only imagine the outcry that would ensue if a politician said that we didn’t need any laws to punish rapists, that public opinion opposing rape would be sufficient to prevent any sexual assault from occurring.

Needless to say, it didn’t work. The treaty was violated almost immediately – by Japan in China, by Italy in Ethiopia, and by the United States in Nicaragua – and within a dozen years of the treaty’s signing, most of the countries that signed it had entered into the Second World War, a conflict which would dwarf the first one in ferocity and end with a mushroom cloud. Following that war, once again there was a wave of repugnance for war and a decision to ‘fix’ the weaknesses of the League of Nations and the Pact of Paris, by given ‘teeth’ to the newly founded United Nations.

UN not equipped to stop the global war system

Well, that didn’t work either. As the proponents of ‘outlawery’ predicted, you can’t use war to enforce peace. Since WWII, millions have died as the fighting has continued unabated, and the very idea of outlawing war has come to be seen as naïve, old-fashioned, and rather quaint – as quaint as the archaic notion of bothering to declare war on a nation before bombing it.

It reminds me of the old saw about smoking: “Quitting smoking is easy; I’ve done it dozens of times.” It is also reminiscent of the commercial I once saw for a nicotine patch, in which a grizzled man looks belligerently at the camera and says, “Don’t tell me to quit smoking. Tell me how.” These examples are made applicable to the campaign to outlaw warfare, when one remembers the fact that the human race is addicted to war. Our warfare system has all the hallmarks of an addiction. Over and over, we swear off our drug, promising ourselves and everyone else that we will never touch the stuff again. And yet deep down we think that we cannot live without it. We aren’t even very discrete about hiding the bottle in the cabinet, or the track-marks under our sleeves.

Treaties do not work

We now know what will not work. Signing a treaty outlawing war doesn’t work. Creating a mass movement that opposes war doesn’t work. Expecting public opinion alone to prevent wars doesn’t work. Threatening nations with sanctions or economic blockades to punish them for fighting doesn’t work. Bombing or invading them to make them quit bombing or invading others only works temporarily – and sometimes not even that, as the recent missile fuselage against Syria aptly demonstrates.

Not a treaty but a world constitution with real enforceable law

What will work? A super –tribunal, as Kellogg hinted at in his speech? Perhaps, but even that is doubtful. If we are to ‘outlaw’ war, then as E.B. White said, “Law is the thing.” Real, enforceable world law – not a treaty, not an agreement, not a solemn promise made with fingers crossed behind our backs. We need law that has been passed by a democratically elected legislature, enforced by a properly constituted executive, and tried by an impartial system of courts. Ending humanities addiction to war is going to involve a massive twelve step program. It means starting from scratch, remaking human society from the ground up. Exactly how we can do this is a mystery. But one thing we can say for sure: it is going to be tough. The toughest thing humanity has ever accomplished. When it is finished, however, we will have something powerful, something that, unlike the Kellogg Briand Pact, will never be forgotten.

Author Contact: Gray Kevin Shephaerd

.